Professor Robert J. Miller’s article “Sovereign Resilience: Reviving Private-Sector Economic Institutions in Indian Country” was published in Brigham Young University Law Review. To review, click here

Category Archives: Information

ILP Professors & their Tribal Ties

ILP Alumni with Concurrent Degrees

Alumni Tribal Court Judges – Pt. 2

Native American Pipeline to Law Workshop at UC Berkeley: Still Accepting Applications

This is a great opportunity for students to learn about law school, admissions criteria, LSAT prep, and more. Registration is free, food and lodging is provided, and a limited number of LSAT Prep courses will be available for participating students. It does not matter which school the student wishes to attend: these sessions are geared to help all students.

Date: June 26-30, 2019

Location: UC Berkeley School of Law

Boalt Hall, 225 Bancroft Way, Berkeley, CA 94720 (map)

For more information, visit: law.asu.edu/pipelinetolaw

Deadline: May 1, 2019

Questions? Contact Kate Rosier at 480-965-6204

Read about current law students who completed one of the Pipeline to Law Workshops and highly encourage others to register and participate. Read their stories.

April Olson (JD ’06) Lunch Lecture – Recording

Guest speaker and ILP alum, April Olson (’06) gave an insightful lecture, “A Story from the Standing Rock protest: Prosecution and defense of a water protector.”

In 2016, the fight for clean water and the indigenous led resistance to the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) caught the attention of the world. At the heart of the movement, was opposition to the DAPL, a pipeline projected to run close to the Standing Rock Reservation that threatened its clean water and sacred sites. No-DAPL demonstrators drew the ire of officials and law enforcement and numerous individuals engaging in peaceful protests were arrested and prosecuted for serious crimes in state and federal courts. This presentation talked about one of the many stories from Standing Rock and will follow the prosecution of one water protector from his arrest to his challenge before the North Dakota Supreme Court. Please see Corrected Opinion in North Dakota Supreme Court No. 20180171 (State v. Herbert) if you want to read more about the case.

To listen to recording, click here.

Student Reflection – Pipeline to Law Initiative

Professor Trevor Reed in ASU Now: Native American view of the Grand Canyon’s centennial celebration

The beautifully colored landscape that many recognize as one of the natural wonders of the world — Grand Canyon National Park — is also a sacred place for many surrounding tribes. ASU Law Professor and Hopi tribal member Trevor Reed provides his insight in ASU Now. Read article here.

Alumni Advice – Udall Alumni

The Indian Legal Program is always looking to expand our ILP family’s opportunities to network and gain experience in the legal profession. By networking with the Udall Foundation, we can show students more opportunities to participate in Indian Law programs across the country. Alumni Chia Halpern Beetso (’08), Julian Nava (’10) Jacqueline Bisille (MLS ’14), all completed the Udall Internship, along with current students Cynthia Freeman (2L), Christina Andrews (3L) and DesiRae Deschine (3L). The ILP asked these six Udall Alumni to share some advice to current or future students through their experience participating in the Udall Summer Internship Program.

“After completing my undergraduate degree, I was accepted into the Udall Foundation Congressional Native American Internship Program,” Sarah Crawford (3L) said. “This opportunity gave me my first hard look at the legislation and policy at play… The Udall Foundation also provided additional opportunities to visit and learn from a variety of agencies, law firms, and organizations that focus on Indian Country policies. The Program also provides housing and travel expenses which greatly reduced the burdens that prevents many Native individuals from pursuing a summer internship in Washington, D.C.”

Q: When did you intern at Udall and why did you apply?

Chia Halpern Beetso: “I participated in the Udall Foundation Native American Congressional Internship during the summer of 2007. I applied because I always wanted to intern in a U.S. Congressional office and heard so many great things about the program. I also had friends who really enjoyed their experiences while participating in the Udall Internship as well.”

Julian Nava: “I was a Congressional Intern through the Udall program in the summer of 2006. I applied because I wanted an insider’s view of our Nation’s federal government i.e. how policies & laws are formed and money is appropriated, especially as it applies to tribal governments and tribal programs. I was also very interested in the history of U.S. laws and policies directly aimed at American Indian tribes, so I thought, what better place to learn about that dynamic (past, present, future) than at the center of U.S. law and policy.”

Cynthia Freeman: “I was a Udall intern in 2006. I applied because the Udall internship program provided a unique opportunity for me to work in Congress and to learn more about tribal laws and policies.”

Jacqueline Bisille: “I interned during the summer of 2014 in the late Senator John McCain’s office. While living in Arizona, I interned with various organizations and a local government on issues that affected Arizona Tribes. While I enjoyed my time with those offices, I never had the chance to work on policy issues that involved the Federal government and Indian Tribes. When I heard about the Udall Internship in D.C., I knew it was an opportunity to not pass up so I prepared my application, sent it in, and waited for the Foundation’s decision.”

Christina Andrews: “I interned summer 2017. I interned at Udall because I wanted to learn about the United States’ legislative process and its impact in Indian Country. I wanted to know if I had a place at the U.S. government area. I applied because of the prestige of being a Udall Intern and the doors it would open up for me.”

DesiRae Deschine: “In 2017, I was a 1L when I was selected for the Udall Foundation Native American Congressional Internship. I wanted the legal work experience within a federal agency and to gain an inside look at the regulatory process of federal Indian law. In addition, I wanted to be a Udall Intern so that I could live and experience Washington D.C. with a cohort of other Native American students.”

Q: What was the experience like and what was the most valuable thing you learned?

Chia Halpern Beetso: “I had the best summer. I was in the office of the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs and was able to help plan and attend committee hearings. I got to see first-hand how legislation is drafted and passed. I was also fortunate enough to work on an issue that my own tribe needed assistance with. The most valuable thing I learned was to take the initiative to pursue my professional goals.”

Julian Nava: “I had a wonderful experience that I will cherish for a lifetime. The most valuable lessons that I learned during my internship was how important relationship building is, including, building relationships with those people who agree and understand your views and interests as well as those people who do not. Your ability to communicate and be inquisitive is vital to a successful experience.”

Jacqueline Bisille: “The experience was unforgettable because it gave me the opportunity to learn more about a career that I wanted to work in. I’d say the most valuable thing I learned was how Congress moves legislation through both chambers. The process is fascinating and continues to challenge me in unique ways each day while working for the SCIA.”

Cynthia Freeman: “The experience was rewarding; it provided me with numerous opportunities to network with tribal leaders and tribal advocates, meet Congressional leaders, and forge lifetime friendships. The most valuable thing I learned was the importance of having tribal representation within Congress, both at the leadership and staff levels.”

Christina Andrews: “The experience was more than I could have ever imagined. I was able to see the place where the Nation’s decisions were made. I learned about how law is made and passed; toured the White House and legislative buildings; helped create a bill and walk it through the process for consideration at the floor; I met many people who are advocating for Indian issues; I learned about being a leader and advocate for Indian Country; and finally, I built a lifelong cohort with other Udallers. We still remain connected.”

DesiRae Deschine: “Interning with the Department of the Interior as a Native American Congressional Intern was invaluable. I received great mentorship and substantive legal work assignments from my internship placement. In addition to the work experience, I was exposed to other federal agencies, congressional offices, and non-profit organizations that share similar goals related to Native American communities and Tribes. Through this experience I strengthened my legal writing skills and as a result felt capable and ready to spend a full-semester in Washington, D.C. as a 3L with the D.C. Externship Program through the Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law.”

Q: Would you recommend this program to other students? If so why?

Chia Halpern Beetso: “I would definitely recommend this program to current students. It is a great chance to have a paid internship in Washington DC which isn’t always an option for many people. You often get to work on Native issues and have opportunities to attend hearings, meetings and receptions with various leaders in Washington DC. It can lead to job opportunities and truly is a learning experience.”

Julian Nava: “I would absolutely recommend this program because this program gives a hands-on experience that will hopefully provide students with a better understanding of how law and policy is formed, how the system works in real time and how they can eventually be a part of that system and/or change.”

Jacqueline Bisille: “I definitely would recommend the internship program to any ILP student thinking about working on tribal issues. In some way or another, a tribal government will likely have to work with Congress or the Administration and it’s good to have an idea of what goes on in DC.”

Cynthia Freeman: “Yes, I highly recommend this program to any student who is interested in learning about federal Indian policy and would like to work in Washington, D.C. As a participant, you will gain valuable insight into the legislative process as it pertains to tribal nations.”

Christina Andrews: “I was intimidated about DC, but now after going through the program, I have more confidence having spent the summer at DC. Also, this program challenged myself as an older student that I still have a lot to contribute, and I plan to do just that.”

DesiRae Deschine: “I absolutely recommend the Udall Foundation Native American Congressional Internship program to students that are interested in learning more about the government-to-government relationship between Tribes and the federal government and working for a congressional office or a federal agency in Washington, D.C. Being a Native American Congressional Intern was a unique experience and through the program I gained access to a network of Native American professionals who are contributing to strengthening Indian Country. Furthermore, I recommend the Native American Congressional Internship program because of the support that the Udall Foundation provides to each student that makes living and working in Washington, D.C. possible.”

Cynthia Freeman (left) in 2006 and DesiRae Deschine and Christina Andrews (right) in 2018

Q: For students who want to apply, what advice would you give them?

Chia Halpern Beetso: “I would advise students to review their essays a couple times prior to submitting the application. Also, to clearly explain why this experience will benefit them in their goal of working on tribal policy and make the connection as to why this internship is the next logical step in their trajectory.”

Jacqueline Bisille: “My advice for students considering in applying is to not procrastinate on your application. I’ve heard that the review committee can tell what applications were lazily put together from others that include well written essays. My last bit of advice for any student considering the internship program would be to go, if accepted, because they will be sharing these experiences with 11 other Native students, and have memories for a lifetime. A few of the Udall interns in my class live in DC and have become some of my closest friends. A bit cheesy, I know, but also one of the best things about the program and why I’m happy to have done it.”

Julian Nava: “Be inquisitive, ask questions (1,000 + perhaps), be involved, explore, be willing to learn, sightsee, be adventurous, network and tell your story. People are very interested in your story. Tell it.”

Cynthia Freeman: “If you are considering applying, then it is very important that you have someone (a professor or mentor) review your application materials. I highly recommend talking with the Udall program or alumni, if you have any questions about the internship program or the application process.”

Christina Andrews: “For students who what to apply, I would advise them to take the application serious. Make sure you give well thought out answers; dig deep for your answers; don’t feel intimidated; and ask questions. Make sure to reach out to others who have gone through the program for help.”

DesiRae Deschine: “Students interested in the Native American Congressional Internship should reach out to alumni of the internship program and the Program Manager to learn more about the program and to receive individualized advice about the application process. Students should also work on their application ahead of time, research the contributions of Morris K. Udall and Stewart L. Udall to Indian Country, and seek out critical feedback on their essay.”

Find out more information about the Udall Foundation’s internships here.

Photos provided by students & alumni.

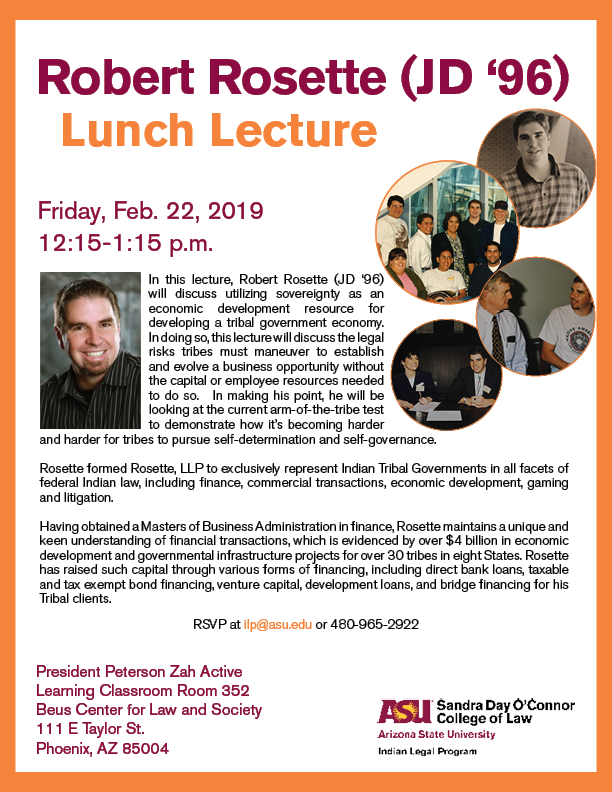

Robert Rosette (JD ’96) Lunch Lecture – 2/22

Free and open to public. Food will be reserved to those who send their RSVP to ilp@asu.edu. Join us!