Our Indian Legal Program alumni have made our school proud by pursuing a variety of different careers in law. For those who decided to go into tribal courts, we asked them to give their advice and share their experiences to help current and prospective students navigate a career in tribal courts or as a tribal court judge.

Tribal court judges from the ILP:

- Meredith Drent (’00) chief justice (2012-present) of Osage Nation Supreme Court in Pawhuska, Oklahoma

- Danielle Ta’Sheena Finn (’17) judge of Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe Healing to Wellness Court in Eagle Butte, South Dakota

- Joseph Flies-Away (’04) judge of the Hualapai Court of Appeals in Peach Springs, Arizona

- Kaniatari:io Jesse Gilbert (’07) chief judge of Hualapai Tribe’s Tribal Court in Peach Springs, Arizona

- Anthony Hill (’06) judge of Gila River Indian Community Tribal Court in Sacaton, Arizona

- Denise Hosay (’07) judge of Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community Tribal Court in Scottsdale, Arizona

- Anthony Little (’76) judge of Yavapai Apache Nation Tribal Court in Camp Verde, Arizona

- Claudette C. White (’05) chief judge of San Manuel Tribal Court in Highland, California

- Christine Williams (’00) of chief judge of Shingle Springs Tribal Court in Placerville, California

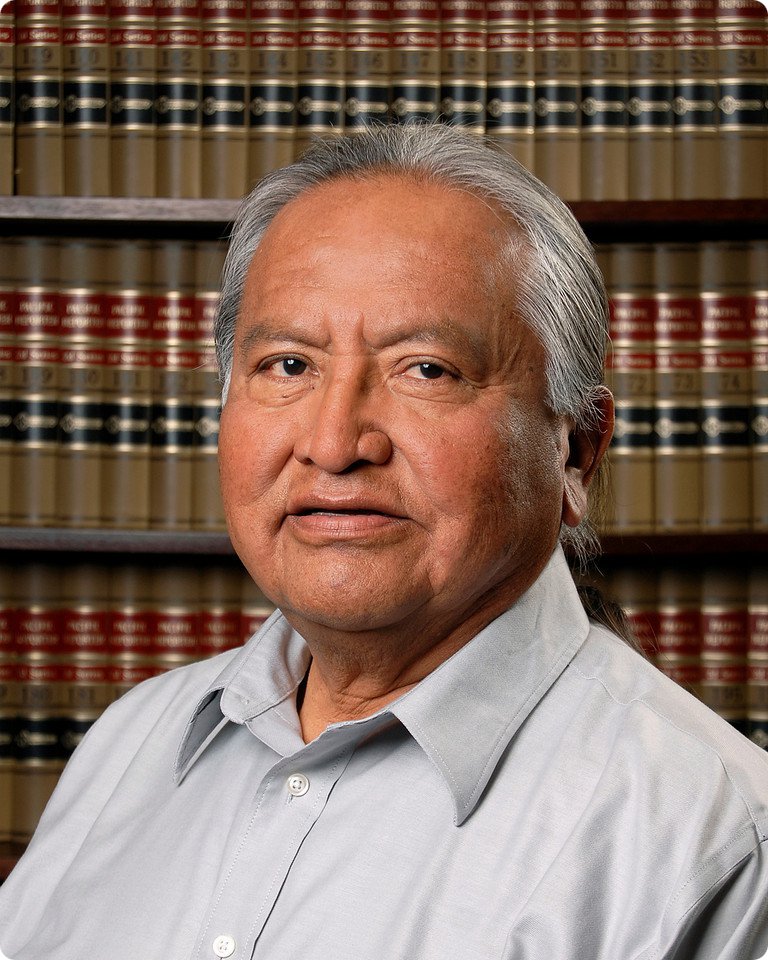

- Herb Yazzie (’75), former chief judge of Navajo Nation (2005-2015) in Window Rock, Arizona

Q: How long have you served as a tribal court judge?

Meredith Drent: I was appointed chief justice in 2012 following the retirement of Chief Justice Charles Lohah and was retained by a vote of the Osage citizenry in 2014 and 2018. Prior to my appointment, I served as an Associate Justice of the Osage Nation Supreme Court following my appointment and confirmation in 2006 and was retained for another four year term by citizen vote in 2010. (The Osage Nation adopted a constitution in 2006, which did away with the centralized council form of government and created a three-branch government. It was an achievement many, MANY years in the making and I suggest you read “Colonial Entanglement” by Jean Dennison to get the full picture.)

Danielle Ta’Sheena Finn : I was appointed in April 2018, so I have been a judge for approximately one year.

I am the chief judge of the Cheyenne River Healing to Wellness Court. I am an Associate Judge for all other courts on Cheyenne River: Criminal, Civil, Children’s, and Involuntary Committal.

Kaniatari:io Jesse Gilbert: I have been the chief judge of the Hualapai Tribe since April 2018.

Claudette C. White: I have served as a tribal court judge for the last 12 years and in May of this year it will be 13 years. I had the privilege of serving my own tribal community, the Quechan Indian Tribe as their chief judge for the last 12 years and have just finished my first year as the chief judge for the San Manuel Band of Mission Indians.

Christine Williams: I was appointed to my first chief judge position in 2010 for the Hopland Band of Pomo Indians in California. I am currently the chief judge for the Shingle Springs Band of Miwok Indians Tribal Court in California and have been since 2012.

Herb Yazzie: I was chief justice for 10 years, roughly, 2005 to 2015.

Q: Why did you choose to pursue this career? What was your pathway to serve as a tribal court judge? Did your time at the ILP impact this decision in any way?

Meredith Drent: In all my work before, during and after law school, I discovered an interest in community-based program development, particularly for tribal courts because —during the formative years of my legal career—I was working in a state where the momentum for tribal justice development had kicked in and many tribes were examining their options.

Community-based development requires an examination of the community’s values. Tribal justice includes the interaction of those values and the law. The judge who walks in and just starts with an examination of the law, or if there is no substantive law, an examination of some other jurisdiction’s law, without examining those community’s values is only doing part of the job.

I got tired of seeing well-meaning (but wholly subscribed to American jurisprudence based on English common law) judges doing part of the job, or well-meaning (but judicially inexperienced) attorneys fail to learn the skill sets necessary to be a judge. So, I committed to better reflecting the community in the work I did and incorporating relevant training and experience. I had…varying degrees of success. To be fair, it’s hard not to turn into a “dogmatic ideologue” (a phrase used to describe me at one critical point in my legal career by a jerk) with clear vision about what you think a program should be and struggle with building consensus among the stakeholders (an absolute must in this work).

I love the law, and rather that work in an adversarial system that often argues in absolutes, I am required to make decisions that reflect the community and its laws, which require flexibility and adaptability.

Before law school, I was a deputy court clerk for the Osage Nation’s court; through that work I met many attorneys who practiced Indian law. I also noticed that the attorneys who appointed as judges had no judicial experience and no training. In law school, I learned about tribal court policy, development, and practice. In practice, I continued to study tribal court development, administration, and evaluation. I went to various trainings (at the time not many were accessible to a baby attorney with billable hours to accrue) to learn the skill sets to create, evaluate, operate, and improve tribal courts. I did find a great community of tribal court judges, practitioners, and champions–some were lawyers like me, but others were social workers, community leaders, professors, and dedicated administrative professionals.

In private practice, I became disillusioned with billable hours, finicky partners, and temperamental clients, and I still loved the work. When I was tribal in-house counsel, I was disillusioned with fair weather colleagues and outdated legal modalities (the Indian law landscape was changing and change is difficult), and I loved the work.

When the opportunity arose to serve as an appellate-level justice for the Osage Nation, I accepted almost immediately and was confirmed by our legislative body. It was a part-time position (you work when there’s a case and our cases are precedent-setting doozies); it was a chance to serve my own community and to work with an experienced (I like to say “delightfully seasoned”) chief justice.

Before law school, all these thoughts about community-based practices and values were nebulous. The ILP gave me focus, community, and perspective. It encouraged a holistic, comprehensive examination of legal principles (at the time it was an emerging methodology). It encouraged creative solutions to complex problems. We were taught to remain grounded, be respectful, and act with integrity, and we were taught to push for change and challenge the status quo. At least that was the lesson I took from it. Others’ mileage may vary.

The ILP produces the newest generation of Native lawyers and judges and I am happy to be one of them.

Danielle Ta’Sheena Finn : I chose to pursue this career because I wanted to serve my People, the Lakota. I believe judges have the ability to make changes within tribes that are done in ethical, sound ways and have extraordinary responsibilities to make just decisions. Before I was appointed unanimously by the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribal Council, I worked as a political appointee, Director of External Affairs, under Chairman Faith’s administration for the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe. My legal work consisted of drafting policies, procedures, resolutions, and codes and I wanted to try something a bit more challenging.

The interview process to become a judge on Cheyenne River took approximately 4 months (From January to April 2018) and it was a very thorough, but rigorous process. Not only was I interviewed on tribal, state, and federal law, I was also tested on my aptitude to speak in my language: Lakota.

My all-time favorite law professor, Professor Robert N. Clinton, served as a Justice for the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribal Court of Appeals and so when I saw the position for a judge open up in Cheyenne River I thought what a great way to walk in one of my role models footsteps. My time at the ILP, being mentored by Professor Clinton, definitely impacted my decision to pursue this exciting career.

Kaniatari:io Jesse Gilbert: I fell in love with litigation work after my second year of law school. I took Intensive Trial Advocacy that summer, and enjoyed the experience. That fall, I did the ILC, and did my first civil trial — which we won — in Justice Court. When I graduated, I really wanted to be a litigator, and I am pleased with the work path I took – it provided me with a great deal of both training and practical opportunities. But after a while, I wanted to move on to the judicial role.

So, after graduating in 2007, I clerked for the Federal Public Defender’s Office in Phoenix for a year. Then I was a deputy public defender for both La Paz County (Parker, AZ), and Maricopa County for around five years. For four and a half years after that I was the Director of Legal Aid for the Colorado River Indian Tribes in Parker. And now I am the Chief Judge of the Hualapai Tribe in Peach Springs.

Claudette C. White: I actually had not set out to be a tribal judge, I went to law school to be a better tribal leader. I had served (2) terms on my tribal council and had hoped to return home to someday serve as our tribal president. However, with my degree in hand, the position opened up and my elected leaders at the time allowed me to interview and selected me as their chief judge.

I had previously served as a member of the Quechan Tribal Council, which gave me excellent insight into tribal government, tribal structures and tribal courts because during the time I served, we had adopted our first law and order code and had implemented the court. I also had served as a tribal court advocate and helped develop training for advocates. Additionally, while I was in law school at ASU, I had been part of the very first Indian Legal Clinic class, which gave me the opportunity to learn about tribal courts, as well as the privilege of representing clients in tribal court. I did that for about (2) years prior to taking the bench.

My time at the ILP hugely impacted my choices and it gave me the opportunity to feel confident that I had the skill set necessary, legal training and network to help guide me through my initial journey as a judge.

Christine Williams: I always remember having a strong sense of justice and the inability to ignore injustice. I am also a notorious rule follower and court forms really get me going so being part of Tribal Justice Systems was a natural fit for me. I knew I wanted to be of service to tribal communities when I attended the Indian Legal Program (ILP) at Arizona State University College of Law and graduated in 2000. The ILP provided me with unique opportunities to study tribal jurisdiction, tribal sovereignty, and also explore practical applications of both Federal Indian Law and Tribal Law in Indian Country. It was through those studies and experiences that I sharpened my vision of increasing tribal justice systems capacity in California.

When I returned home to California after graduation, it became clear that the work relating to tribal justice in California, a Public Law 280 state that has been all but overlooked by the Federal Government, was going to be court development work in tandem with actual dispute resolution. There are over 100 federally recognized tribes in California and most of them without their own justice systems (tribal courts). As I progressed in my career serving tribes in California, I realized that, in all likelihood, if I were to become a tribal judge, I would not be “taking the bench” for a fully designed and staffed system with existing policies, procedures, rules and forms. A few Tribes did have well developed systems, but most were just starting to develop their tribal courts or even just considering that option from a feasibility standpoint. There was an exciting opportunity for nation building and community building. I saw my mission of service to California Indian Country as it relates to tribal courts as supporting the creation of pathways for tribes to fully exercise their sovereignty by resuming their own administration of justice.

My degree in Federal Indian Law from the ILP is a critical piece of the knowledge I use to serve the Tribes I have been a chief judge for. I built upon that knowledge base over the years to become who I am today as a Judge serving the Tribal Community in California. I will always credit the ILP for providing me the opportunity to start my journey into the representation of and the service to Tribes with such a solid and strong foundation.

Herb Yazzie: I never really planned to be a judge. I started out my legal career interested in representing the poor. Those who needed legal services and couldn’t afford legal counsel. I started out in legal services. Did that for approximately 10 years. Then my other interest was to help the people, meaning the Navajo government. After serving initial years and representing in southern Utah and northern Arizona, I ended up with the Navajo government and what was newly established Department of Justice. I ended up becoming the Attorney General and then I left to work for the Yavapai Apache Nation in Camp Vere for two to three years. I was then recruited back to Navajo Nation to help on the legislative to develop and implement legislation laws for use—education and traditional Navajo law. Then I was recruited to be chief justice.

When I was in school at ASU, the teaching of Indian law was brand new. Indian Law and ILP was just getting started. I really don’t recall working that extensively of what is now the ILP.

Q: What have you learned in your current position that has been different from positions that you’ve previously held?

Meredith Drent: First, not everyone can be those Native Nations that have (a) held onto their language (b) held onto their traditions with few deviations and (c) have governmental policies firmly rooted in cultural values. Some of them are still clawing their way out of the footnotes to show they are a living people. Some of them are using their own voices after decades (or centuries) of colonial auto-tuning. They deserve their seats at the table. Help make room for them.

Second, it is one thing to discuss using tribal principles in justice administration, and it’s another when you actually do it. Western colonial principles can run deep for those tribes that adapted those principles (sometimes by necessity, sometimes by choice) and tinkering with those principles can be messy.

Third, look to tribal law first. If there isn’t a law then extrapolate from other tribal sources (laws, policies, manuals, memos, events, activities, services, etc.). I shouldn’t have to write that, but based on the sheer volume of pleadings based on state law or citing state law and policy, it needs to be written.

Fourth, you should have a passion for public service and serving a community through its court before you enter this line of work. It doesn’t have to be the most meaningful thing in your life (read the Atlantic article about “workism”), but it does have to be meaningful.

Fifth, the best judges adapt–to different laws, new governing bodies, evolving technologies, and new techniques.

Sixth, compassion fatigue and vicarious trauma are real things and for Natives working in tribal courts, it gets real. And difficult. And heartbreaking. Pay attention to it and get help.

Finally, it’s important work, rewarding work, but not glamorous work. Ambition is rewarded when you get reappointed or retained by popular vote, when your state and federal counterparts treat you as a colleague, and when someone uses your opinion as a good example of a concept. There isn’t really a Super Lawyers Magazine for tribal court judges.

Danielle Ta’Sheena Finn: In the position I am in, I see all matters in court, some days I think absolutely nothing can surprise me. I see the good, the bad, and the really bad, but being able to figure out solutions and make tough decisions, makes me feel very valuable to the community, the tribe, and my People. I have learned in my current position that even some of the worst situations can have silver linings. In the past, I worked on the legislative side of the tribal government, but now I am on the judicial side, which proves to be just as important to a functioning, ethical government.

Kaniatari:io Jesse Gilbert: It’s a different role. When I was a practicing litigator – I was always pushing my client’s position. But now I have no clients, and I enjoy being free from advocating for one side over the other. My concern now is more for the process to make sure that everyone gets their fair shake in the system, and to try to improve the processes we use to optimize efficiency.

Claudette C. White: I’ve learned that our people give so much trust to our tribal judicial systems and they expect accountability as a result of it. I’ve seen first-hand how some of our people are mistreated in the state system and how we, as tribal judicial officers, have the responsibility of not only adjudicating matters but also the responsibility of educating and empowering the people we serve by teaching them about differences in our system or by educating them about their responsibilities as a party before the court. In addition to that, I’ve learned that often tribal judges aren’t given the same respect as our counter state and federal colleagues so we have the additional responsibility to educate them and the public about complex jurisdiction, questionable subject matter and tribal sovereignty because of the huge impact those issues have on what we do.

Christine Williams: The most important lesson I have learned from my position as a Chief Judge as it contrasts to my work as a tribal attorney is how to listen. As an attorney, especially in litigation, you are developing advocacy skills. How to use the facts, and laws and statement and arguments of others to advance a specific interest of your client. As a judge, you are not on either side of an argument, in fact you make no argument at all, you make decisions and issue orders and rulings. It’s different. You are not advancing the interests of either side, but rather the larger interests of justice for the community you serve. It can be daunting. What I have learned is that justice is found in the truth and the truth is discovered by listening. Not, listening while thinking of a response, not, listening as you compare what is being said to evidence in the file, just listening for the content of what is being said. It can be a difficult transition for some of us lawyers to make. If we receive any training for court in law school it is how to speak, not how to listen. I have learned that everyone, (everyone!) has a story, and it’s my job to hear that story…while keeping the court calendar on track of course.

Herb Yazzie: When I was chief justice, I learned that resolving disputes among your own people is difficult because the resolution of dispute is unfortunately administered by the use of a foreign system. And it makes it difficult. What I learned is that the Navajo Nation is developing the ever evolving system in modern Navajo, Peacemaking system needs to be supported by the people and government. One sense of justice is achieved if you leave the traditional system. Changing from a system that was imposed by the US government into something that is more Indigenous and more compatible with Diné values is a difficult job because of doctrination. In order for people to survive in the modern world, they need to feel comfortable, their traditional values is being observed and used in today’s world. Use of adversarial system is detrimental to future system.

Those of us who’ve had the difficult pass of resolving disputes have realized many years or doctirnation or colonization is mighty difficult to enhance the traditional legal principles and values of the people because their adherence to traditional value that we were all taught. My thought is law school especially those who are near Indian Nations, they should make a special effort to have the Indigenous students know that there is an alternative to what is being taught in law school, an alternative justice system and it’s their own tribal system if they wish to go back to their own people and their own government, especially to resolve disputes.

Q: What advice do you have for students interested in a position as a tribal court judge?

Meredith Drent: Please don’t take the job on a whim. Earn the title. Don’t just study law; study art, history, and culture. Read books by judges for judges. Attend specialized training for judges, for court clerks, and for court administrators. Learn how a court system works. Learn the court clerk’s job and the court administrator’s job. Chief judges are often administrators so you need to know how to run an office. If you can, help develop a court. Observe other courts and other judges. Learn the tribe’s language if you can. Keep up with technology. Act with integrity. Treat others with respect. Find fulfillment in other parts of your life. Never put anything online that you don’t want people to see; potential employers, potential leaders, and the general public will Google you. Learn mindfulness and self-care. Take self-defense. Eat your vegetables.

Danielle Ta’Sheena Finn : My advice would be to clerk for a tribal court judge; come clerk for me! I’d advise students to try out all areas of law to find out what suits their interests best and don’t settle for a job that doesn’t make you feel valuable, because a Native in law is VERY valuable. You are valuable!

Kaniatari:io Jesse Gilbert: I think it is very important for trial-court judges to have litigation experience. Learning how to lay foundation, knowing the rules of evidence and procedure, and effectively planning a direct or cross-examination – those are invaluable tools for litigators, and the system works better if the judges also have that background.

Claudette C. White: I would tell anyone who is interested to learn all you can, participate in moot court, create a large network of colleagues, mentors and resources. Take the time to know your own tribe and understand that structure first so that you go in with some general knowledge and to remember that tribal judicial systems are unique and that the tribe has the authority and autonomy to create a judicial system that is reflective of their own tribal values and know that as an ASU ILP Alum, you’ll have an incredible extended network of people who are there to support you and help you!

Christine Williams: Do it! We need more qualified and dedicated tribal court judges, at least we do in California. To prepare to take on that role, find mentors, observe tribal courts when you can and complete trainings. As the director of the Tribal Justice Project at UC Davis School of Law, I am part of a team working to provide training for those interested in becoming a tribal court judge or working as tribal court personnel. Our tribal court judge training model focuses on knowing the community you serve with an emphasis on judicial conduct. For law students, I think it is important to consider that when you take the bench as a tribal court judge, at least this is true in the communities I have served, you bring your entire reputation to that role. Not only your professional reputation, your entire reputation as a person as you are known to that community. That is not to imply that judges need to be perfect or all-knowing or even right all the time. However, judges are leaders in the community and their conduct is publicly monitored. Rather, you must be prepared to thoughtfully consider your conduct in ways you may not need to in an attorney role. The community must be able to trust you.

Herb Yazzie: Advice to new generation of Indian lawyers, I would say my advice while you’re learning the in’s and out’s, the mechanics and procedural policies of American law, always keep in mind that the people — Indigenous people would prefer the use of their traditional law based on their tribal value system. Always learn from the elders and see how those traditional values and legal principles can be applied to modern indigenous government. Otherwise the simple application of foreign concepts is not really helping Our People. Simply accepting foreign system causes problem, the adversarial system can be detrimental to the justice as envisioned by Indigenous People. More of a restorative justice rather than adversarial system to achieving justice. Learning and applying what I learned in law school always made me feel uncomfortable. Newcomers always try to learn traditional justice and apply that because it’s more acceptable to the People.

Q: Please share your thoughts about the role of tribal courts in tribal communities.

Meredith Drent: Tribal courts present unique opportunities to resolve disputes and (if they have the authority) to consider important government practices and policies in a Native context. For example: punishment may have different meanings in a particular community; value is ascribed to acts for purposes of child support or restitution; or government officials have duties unique to their office based on cultural norms.

Courts should strive for independence, financial stability, transparency, safety, access, accountability and respect. That’s a lot of plates to spin, which is why it is critical that governments treat their courts as partners in governance.

Danielle Ta’Sheena Finn : Essential. Tribal courts establish safety, equality, and fairness in tribal communities.

Kaniatari:io Jesse Gilbert: I think they are important because it is one manifestation (among others) of Tribal Sovereignty. But I also think that Tribal Courts have an obligation to maintain traditional notions of peacemaking and justice.

Christine Williams: I see the role of tribal courts in tribal communities as completing the circle of sovereignty for tribes. To create and utilize a “tribal justice system” is really a community defining what their own standards are around individual conduct and accountability. Laws are social constructs that should reflect the community values. Determining what conduct is acceptable, and what conduct constitutes a violation of the community values defines that community for their own benefit and as a statement to other communities as well. It’s a fundamental way of saying, “this is who we are, this is what we believe, we define ourselves.” Having a way to respond to unacceptable conduct as defined by the tribe through a tribal court, or to resolve disputes between community members through a tribal court, is a critical expression of sovereignty. It is the accountability piece of the justice system, but it is more than that as well. Tribal Courts can restore balance to individuals and the community through well-crafted restorative remedies and court processes that reflect community values that promote accountability to the community and each other. By utilizing tribal courts to intentionally and thoughtfully respond to conflict with remedies and approaches that are infused with community values, tribes strengthen their own sovereignty, completing the circle.

Q: Anything else you’d like to add?

Meredith Drent: Courts are service providers, not revenue generators. Court officers and personnel hold a position of trust with the community. A bad decision is not always the same as a bad act.

Tribes, look for judges who express knowledge of and support for your values, go out of their way to be informed, research and write well, ask good questions, learn and use technology, and can withstand scrutiny by their peers, community members, and appellate judges.

Christine Williams: It is an absolute honor to serve as a judge for communities that I love. I try every day to bring my best to what I do. I am grateful to have had all the experiences I did in my time in the ILP. I am proud to be a part of the legacy of the Indian Legal Program at Arizona State School of Law. I am devoted to having the work I do respect the mission and reputation of the ILP. Go Sun Devils!

Herb Yazzie: I went to law school straight from Navajo Nation down to Tempe. I spent all those years — undergrad then to law school — and I must admit after looking back on it, I always felt uncomfortable about what I was being taught. After becoming a lawyer and a judge, I have learned why I was always so uncomfortable. It was because all that I was being taught was totally different from what my grandma was teaching. One has to learn how to adjust and adapt and how to stand strong for your own people’s value system. That’s a lifetime experience, I believe.

I really developed an attitude. I felt I’m not going to read the analysis and these reports done by anthropologists about my own people. Really got a distaste for that. I had shouting matches with professors.

People who wish, especially the young Diné students coming back to the rez, your job of giving legal advice, helping resolve disputes …remember they will always see you as an educated system and they expect you to counsel the younger ones. And that may mean explaining legal concepts, legal principles, and you will be most effective if you learn how to explain those in the Navajo language. If you mix the two languages (English and Navajo) and try to explain, most likely you’re going to confuse people. Do the best you can to explain entirely in the Navajo language.

Tribal court associates from the ILP:

- Nikki Borchart Campbell (’09) executive director at National American Indian Court Judges Association and both

- Allyson Thomas (’05) court solicitor at Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community in Scottsdale, Arizona

- Kim Dutcher (’01) court solicitor at Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community in Scottsdale, Arizona

Q: Why did you choose to pursue this career? What was your pathway to serve in the tribal court? Did your time at the ILP impact this decision in any way?

Nikki Borchardt Campbell: I chose to pursue this direction by chance, because my husband and I had moved to CO. I really love nonprofit v private practice, because you are able to choose a mission that you are passionate about. My work at a national nonprofit allows me to provide a concentrated focus on tribal justice initiatives and tribal court capacity building.

My time at the ILP prepared me to work within tribal courts and to help train tribal court judges and tribal justice personnel. I particularly value the community and relationships. The ASU ILP community allows me to continue to reach out to our alums, judges, and attorneys to understand the issues and innovations that are happening on the front lines.

Q: What have you learned in your current position that has been different from positions that you’ve previously held?

Nikki Borchardt Campbell: This work is really interpersonal, and I have the opportunity to interface with tribal judges, state judges, federal judges, court personnel, and other individuals working in the justice community. My other positions were focused on direct client representation, so I had a much limited exposure to work within and for our communities.

Q: What advice do you have for students interested in a position in tribal court or as a tribal court judge?

Nikki Borchardt Campbell: I would suggest that they learn as much as possible about the foundational principles of law, especially tribal law. You will need additional training after law school — all judges should go through rigorous judicial training prior to or very shortly after taking the bench. Care about the people. Focus on learning the issues that affect your communities, and do not limit yourself to thinking that working as a tribal judge is focused purely on judicial work. Most of the very great judges care deeply about their communities and are very great leaders who effectuate and implement change.

Q: Please share your thoughts about the role of tribal courts in tribal communities.

Nikki Borchardt Campbell: Tribal courts and tribal judges are on the frontline of applying justice within our communities; yet, they also have the power to heal our communities and protect our sovereignty. Our communities face very real challenges. The co-occurring factors of substance abuse, mental health, and domestic violence affect many of our communities and often lead to unsafe communities and broken families. Many tribal courts and the collaborative justice departments within their tribes are focusing on addressing these issues in order to have safer communities, healthier families, and safe children

Our work at NAICJA allows us to take a multidisciplinary approach to training our community — we strive to provide cutting-edge training to all our tribal court and state counterparts so that they may identify appropriate interventions for all individuals and families appearing before their bench.