Pedro Pizano. Pedro is a Fellow in International Criminal Law and Human Rights Journalism at the McCain Institute for International Leadership. He assisted with four Voz de las Víctimas trainings in Puebla, Mexico City, Chihuahua, and Phoenix.

Two days before I was set to travel to Chihuahua in 2019, a Mexican-American family, including six children, 7 months- to 10 years-old, at least one of which who was shot in the back, was murdered. A year later, no one had been convicted of the crime, and three more suspects were arrested last month for a total of 20 suspects.

Then came the femicides of Ingrid Escamilla, 25, and Fátima Aldrighett, 7, who were brutally murdered and made front-page news; or the 19 murdered in January 2021, for which 12 police officers were arrested.

Add to that that the 1,006 women who were killed in Mexico and the 34,500 murders that were committed in 2019. Less than 25% of crimes are reported. Of those, only 20% are investigated and 2% result in convictions. That means that, of the ones that are reported, in only twenty of the murders of women out of 1,006, would they find and convict those responsible. Twenty.

To attempt to address part of these long-standing issues, Mexico enacted a sweeping judicial reform in 2008. It became the 15th country in Latin America to switch from a written inquisitorial system to an oral and adversarial criminal law system.

The idea behind an oral adversarial criminal law system is that it is fairer and more transparent. Instead of white hemp-threaded unmovable judge-led prosecution files—where removing a page, missing a stitch, or leaving unmarked hand-filled space between paragraphs, would get the evidence thrown out—, an oral adversarial system ensures that every piece of evidence, including witnesses, are contested and aired in open court.

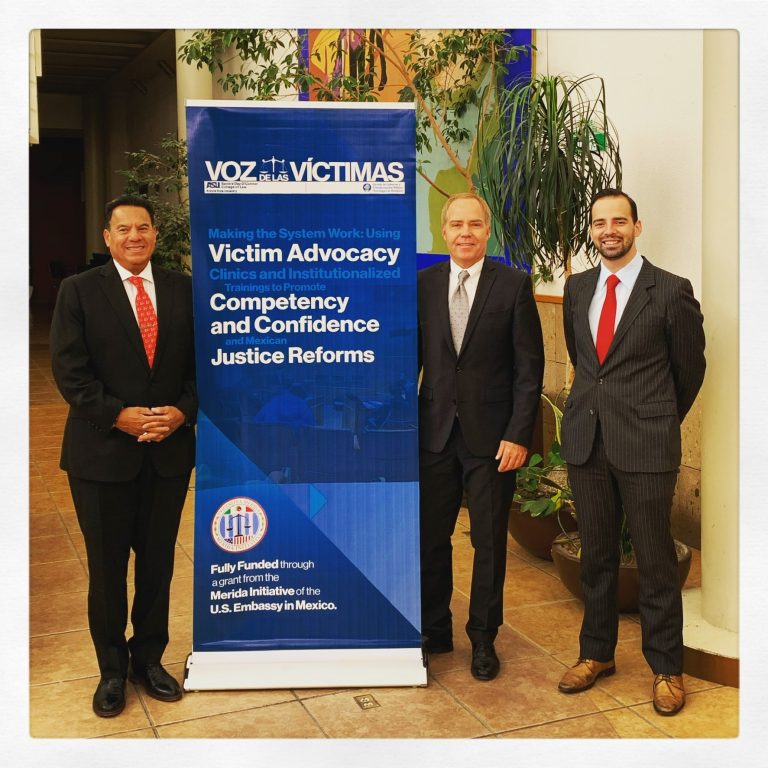

To help with these reforms, the Merida Initiative of the U.S. Embassy in Mexico gave Arizona State University a $2.8 million-dollar grant to train prosecutors, judges, victim’s advocates, and lawyers in the new system. This was part of a $300 million-dollar U.S. initiative.

“We have trained 803 prosecutors, judges, defenders, victim advocates, students, and professors and established six legal clinics in Mexico,” said Evelyn Cruz, a clinical professor of law at the Sandra Day O’Connor Law School at Arizona State University, who led the grant.

“The Clinics have contributed 10,000 hours of pro-bono service to more than 400 crime victims and 1,600 people have attended our events. It has been highly successful and well received by all participants,” said Professor Cruz.

In the three-year period, Arizona State University and the Tecnológico de Monterrey have established a sustainable training program, Voz de las Víctimas, to address the changes in the judicial system.

Participants in the 33 workshops got to practice their oral and adversarial skills. Some federal judges, prosecutors, and defenders had never spoken in open court. They had never seen a cross-examination, least of all practiced it. This program gave them the space to do that.

“I developed the training program with my Mexican counterparts to provide practical hands-on experiences and the type of quality feedback that litigators receive in the United States,” said Tim Nelson, the lead trainer and former Chief Deputy Attorney General of Arizona, who has trained 4,500 people over the past 10 years.

“They get to practice every part of an oral trial, receive immediate verbal feedback from their trainers and videotaped critiques from a different trainer, and then can apply the feedback into the same skills at a full mock trial at the end of our program,” continued Mr. Nelson. “Some of them have never had this type of learning-by-doing education before and really flourish. They end up thinking differently about what it means to prove a person guilty beyond a reasonable doubt, and they better understand the importance of the reforms,” he concluded.

The participants have expressed their satisfaction with the trainings and the quality of their oral rhetoric and grasp of the new system has markedly improved. The trainers focused on promoting learning spaces and abilities, rather than imposing solutions or arguing that the American system is better. In fact, the Mexican criminal law system might be better in that it has Victims’ Advocates who can examine witnesses and evidence.

“This way of teaching and training criminal system actors is so much better,” said Julián Gudiño, professor of criminal policy at the Tec de Monterrey and criminal litigator, who was first a participant and has now led four trainings. “The methodology used in the workshops breaks with the traditional way of imparting knowledge, since not only is the content of the topic presented, but it is exemplified and the trainees are allowed to do it themselves. This is a practice that helps them feel that “making mistakes” is not wrong; on the contrary, it helps them assimilate them and correct them.”

“These learning spaces have been essential to strengthen the human and professional relationships of all the participants so that the criminal system works better for everyone and for society,” said Doctor Juliana Vivar Vera, full-time law professor at the Tec de Monterrey campus in Puebla, Mexico, who has led nine different trainings.

The backlash

The adversarial system may lead to a short-term disruption of law and order. More defendants might be released and the state’s institutions might be perceived to be weaker as the judges no longer control the process.

In Colombia, when they switched to an adversarial system between 2002-2008, the backlash was immediately felt. Colombia was the 13th country to switch to an oral adversarial system in the region. When the forever drug wars revamped in 2010, people felt that they needed to go back to the old system which was more effective at putting drug dealers behind jail, or so people thought. It was not true.

In Honduras, Peru, and Ecuador, to name three, the same backlash happened. It is happening now in Mexico.

In January 2020, the current government in Mexico introduced reforms to weaken the adversarial system. A draft was leaked and the reforms have been dialed back into two packages. They would still hamper the prosecution’s efforts, get rid of control judges, limit the rights of victims to appeal decisions and investigate, and limit the right of the accused to remain silent by allowing negative inferences. It has some positive reforms too such as: a reform of preventive detention, the independence of the national guard, and fuller reparations for victims.

“The two proposed reforms are a mixed bag, but they do hamper the continued development of the transition to an adversarial and oral system,” said Ignacio Hernandez Ordoñez, a professor of criminal procedure at the National University of Mexico (UNAM), who is not involved with the grant or the reforms.

While the proposed reforms are currently postponed due to the pandemic, according to Hernandez Ordoñez and Claudia Peña, the national Voz de las Víctimas coordinator, other countries’ examples of backlash indicate they will eventually pass in one form or another. It should be just a blip in the continued development of the rule of law in Mexico.

In one recent poll, they asked current prisoners whether they felt their conviction have been just and clear. Sixty-one percent of those convicted under the new system—where they can see the evidence against them, confront witnesses, and cross-examine live witness—felt it was just, as opposed to 22% under the old inquisitorial and written system.

“The 2008 reforms were a great advance for our country in terms of not only justice but also for the effective protection of human rights and especially in the efforts to eradicate torture,” said Judge Magistrate Angélica Sánchez Córdova of the Superior Tribunal of Justice of Chihuahua. “The current reforms,” she told me, “represent a setback precisely on those issues that motivated the [2008] reform and it implies great violations of due process and fundamental rights.”

The participants in our trainings will have learned how to throw away their thread and needles. They will now thread the argument in open court rather than on a stale and dead piece of paper.

The 12 police officers arrested for the murder of the 16 Guatemalan migrants as well as some of the 20 suspects of the murders of the Mexican-American family—and more and more defendants accused of femicide—, must soon face their day in court. A prosecutor will have to accuse them orally and they will have the right to contest every piece of evidence. In the end, their deserved punishment should be more just, and justice in Mexico, defendant by defendant, shall have been better served.